Lake Kivu is one of Africa’s strangest bodies of water. An unusual set of properties make it an intriguing subject for scientists, as well as a potential source of peril and prosperity for the millions of people living nearby.

Kivu doesn’t behave like most deep lakes. Typically, when water at the surface of a lake is cooled — by winter air temperatures or rivers carrying spring snowmelt, for example — that cold, dense water sinks, and warmer, less dense water rises up from deeper in the lake. This process, known as convection, generally keeps the surfaces of deep lakes warmer than their depths.

But at Lake Kivu, circumstances have conspired to block this mixing, giving the lake unexpected qualities — and surprising consequences.

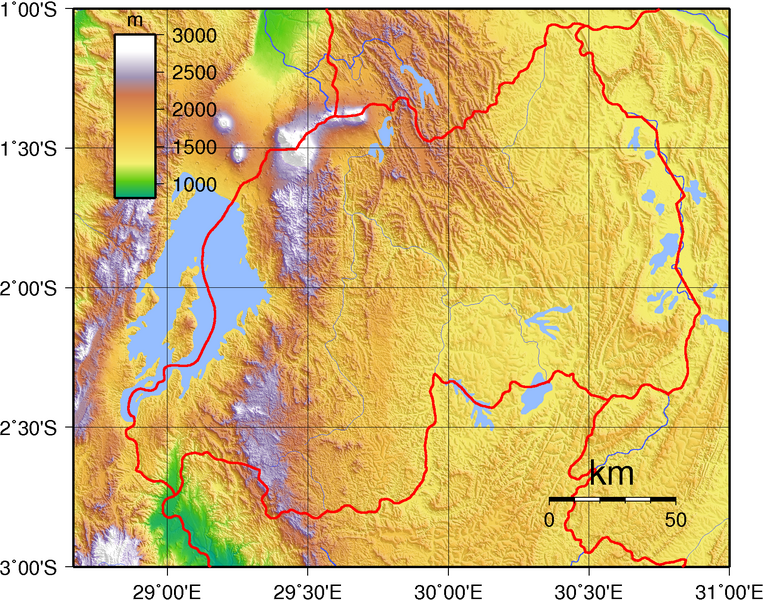

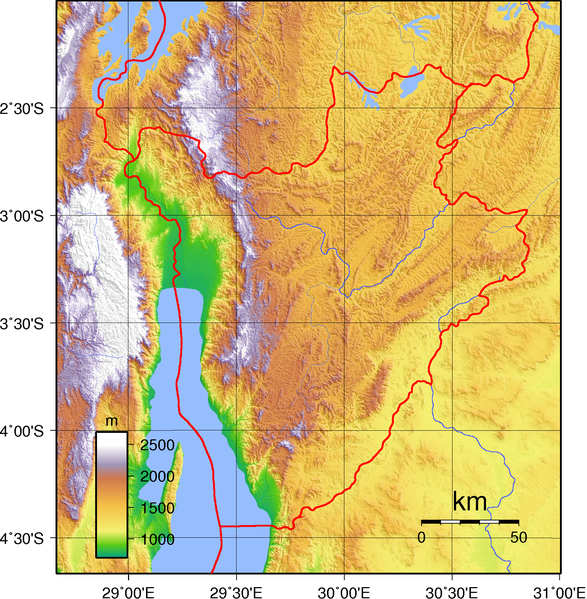

Straddling the border between Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kivu is one of a string of lakes lining the East African Rift Valley where the African continent is being slowly pulled apart by tectonic forces. The resulting stresses thin the Earth’s crust and trigger volcanic activity, creating hot springs below Kivu that feed hot water, carbon dioxide and methane into the lake’s bottom layers. Microorganisms use some of the carbon dioxide, as well as organic matter sinking from above, to create energy, producing additional methane as a byproduct. Kivu’s great depth — more than 1,500 feet at its deepest point — creates so much pressure that these gases remain dissolved.

This mixture of water and dissolved gases is denser than water alone, which discourages it from rising. The deeper water is also saltier due to sediment raining down from the upper layers of the lake and from minerals in the hot springs, which further increases the density. The result, says limnologist Sergei Katsev of the University of Minnesota Duluth, is a lake with several distinct layers of water of sharply different densities, with only thin transition layers between.

The layers can be separated roughly into two regions: one of less-dense surface water above a depth of about 200 feet and, below that, a region of dense saline water that is itself further stratified, says Alfred Wüest, an aquatic physicist at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne. There is mixing within each layer, but they don’t interact with each other. “Just think of the entire water mass sitting there for thousands of years and doing nothing,” says Wüest, author of a 2019 article in the Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics surveying convection in various lakes of the world, including weird outliers like Lake Kivu.

But Lake Kivu is more than just a scientific curiosity. Its unusual stratification and the carbon dioxide and methane trapped in its deeper layers have researchers worried that it could be a disaster waiting to happen.

The unique makeup of Africa’s Lake Kivu prevents the mixing typically seen in other deep lakes, leading to unusual stratification of the waters. There are distinct density differences between each layer. The sharp transition between two of those layers is shown here, with the lower, warmer, saltier water below (red) and the cooler, fresher water on top (blue). The boundary between the two layers is just a few centimeters thick.

About 1,400 miles northwest of Kivu, a crater lake in Cameroon known as Lake Nyos similarly accumulates and traps large amounts of dissolved gas — in this case carbon dioxide — from a volcanic vent at the bottom of the lake. On August 21, 1986, the lethal potential of that gas reservoir was demonstrated in spectacular fashion. Possibly due to a landslide, a large amount of water was suddenly displaced, causing the dissolved carbon dioxide to rapidly mix with upper layers of the lake and release into the air. A large, deadly cloud of the gas asphyxiated about 1,800 people in nearby villages.

Events like this are called limnic eruptions, and scientists fear that Kivu may be ripe for a similar, even deadlier event. Nyos is a relatively small lake, measuring a little more than a mile long, just under a mile wide and less than 700 feet deep. Kivu is 55 miles long, 30 miles across at its widest point and more than twice as deep as Nyos. Because of its size, Katsev says, Kivu “has the potential for a major, catastrophic limnic eruption where many cubic miles of gas would be released.”

Limnic eruptions can occur for two reasons. If the water becomes completely saturated with dissolved gases, any additional carbon dioxide or methane injected into the lake will be forced to bubble out of solution, rise and be released into the air. Eruptions can also be caused when something forces the deep water with its dissolved gases to mix with the layers above, reducing the pressure on the gases and allowing them to quickly come out of solution and escape, similar to the effect of shaking a can of soda and then opening it.

While a landslide of the scale suspected in the Nyos eruption might not cause enough mixing at Kivu, due to the lake’s size and depth, there are several other possible triggers. Kivu is in a seismically active area, so an earthquake could generate waves in the lake that would mix the layers enough to release the trapped gases. Climate is also a potential culprit. At least one past eruption discovered in the sediment record appears to have been caused by drought that evaporated enough water from the top of the lake to reduce the pressure at the lower levels and release the dissolved gases. Lowered water levels during dry periods could also leave Kivu more vulnerable to disruption from particularly heavy rain events. They could flush enough built-up sediment from the dozens of streams feeding into the lake to cause the layers to mix, MacIntyre says.

The chances of such a sequence of events may go up as the planet warms, MacIntyre says. Climate change will bring more rain to East Africa, and “it’s going to come in the form of more extreme rain events with bigger intervals of drought in between.”

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/explosive-hazard-hiding-african-lake-180976024/