I read an article in the October Scientific American last night called: What we learned from AIDS.

The Author is William A. Haseltine: is a former Harvard Medical School professor and founder of the university’s cancer and HIV/AIDS research departments. He also serves as chair and president of the global health think tank ACCESS Health International. He has founded more than a dozen biotechnology companies and is the author, most recently, of A COVID Back to School Guide: Questions and Answers for Parents and Students and A Family Guide to COVID-19: Questions and Answers for Parents, Grandparents and Children

This link is to the article. I think you get a couple of free articles a month at SciAm, so you might be able to read the whole thing:

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/lessons-from-aids-for-the-covid-19-pandemic/

If you can’t, here is the bit I found most interesting:

“Vaccine Challenges

Early observations of how HIV behaves in our bodies showed the road to a vaccine would be long and challenging. As the outbreak unfolded, we began tracking antibody levels and T cells (the white blood cells that wage war against invaders) in those infected. The high levels of both showed that patients were mounting incredibly active immune responses, more forceful than anything we had seen for any other disease. But even working at its highest capacity, the body’s immune system was never strong enough to clear out the virus completely.

Unlike the hit-and-run polio virus, which evokes long-term immunity after an infection, HIV is a “catch it and keep it” virus—if you are infected, the pathogen stays in your body until it destroys the immune system, leaving you undefended against even mild infections. Moreover, HIV continually evolves—a shrewd opponent seeking ways to elude our immune responses. Although this does not mean a vaccine is impossible, it certainly meant developing one, especially when the virus hit in the 1980s, would not be easy. “Unfortunately, no one can predict with certainty that an AIDS vaccine can ever be made,” I testified in 1988 to the Presidential Commission on the HIV Epidemic. “That is not to say it is impossible to make such a vaccine, only that we are not certain of success.” More than 30 years later there still is no effective vaccine to prevent HIV infection.

From what we have seen of SARS-CoV-2, it interacts with our immune system in complex ways, resembling polio in some of its behavior and HIV in others. We know from nearly 60 years of observing coronaviruses that a body’s immune system can clear them. That seems to be generally the case for SARS-CoV-2 as well. But the cold-causing coronaviruses, just like HIV, also have their tricks. Infection from one of them never seems to confer immunity to reinfection or symptoms by the same strain of virus—that is why the same cold viruses return each season. These coronaviruses are not a hit-and-run virus like polio or a catch-it-and-keep-it virus like HIV. I call them “get it and forget it” viruses—once cleared, your body tends to forget it ever fought this foe. Early studies with SARS-CoV-2 suggest it might behave much like its cousins, raising transient immune protection.

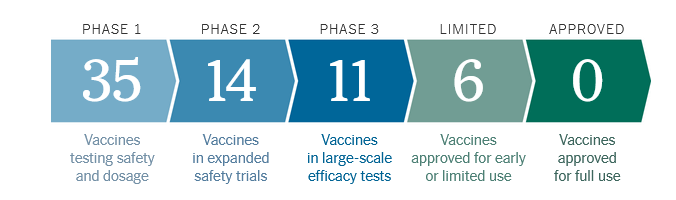

The path to a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine may be filled with obstacles. Whereas some people with COVID-19 make neutralizing antibodies that can clear the virus, not everybody does. Whether a vaccine will stimulate such antibodies in everyone is still unknown. Moreover, we do not know how long those antibodies can protect someone from infection. It may be two or three years before we will have the data to tell us and any confidence in the outcome.

Another challenge is how this virus enters the body: through the nasal mucosal membranes. No COVID-19 vaccine currently in development has shown an ability to prevent infection through the nose. In nonhuman primates, some vaccines can prevent the disease from spreading efficiently to the lungs. But those studies do not tell us much about how the same drug will work in humans; the disease in our species is very different from what it is in monkeys, which do not become noticeably ill.

We learned with HIV that attempts to prevent virus entry altogether do not work well—not for HIV and not for many other viruses, including influenza and even polio. Vaccines act more like fire alarms: rather than preventing fires from breaking out, they call the immune system for help once a fire has ignited.

The hopes of the world rest on a COVID-19 vaccine. It seems likely that scientists will announce a “success” sometime this year, but success is not as simple as it sounds. As I write, officials in Russia have reported approving a COVID-19 vaccine. Will it work? Will it be safe? Will it be long lasting? No one will be able to provide convincing answers to these questions for any forthcoming vaccine soon, perhaps not for at least several years”