The successful predator, which has decimated bird populations on Guam, lassoes its body around poles in order to propel itself upwards.

When biologists found three locally endangered Micronesian starlings dead in their nest box on Guam in 2017, the culprit was obvious. The birds are a frequent target of invasive brown tree snakes. The confounding part was how a snake managed to get into the nest in the first place. The nest box sat at the top of a steel duct pipe that scientists thought was too large for the brown tree snake’s usual climbing tactics.

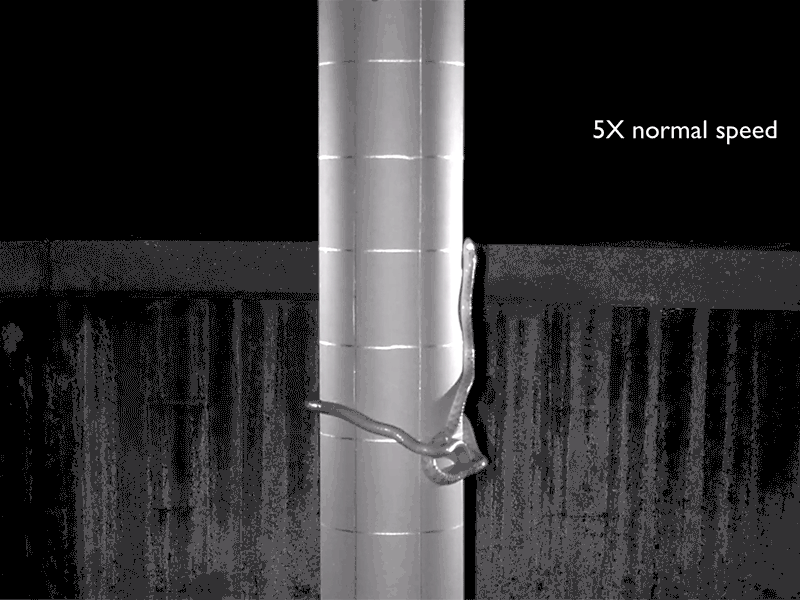

But an infrared trap camera pointed at the nest provided CCTV-like time lapse footage of the break-in: a snake had looped its body around the duct pipe and squirmed to the top in just over 15 minutes. It was the first time that wildlife biologists Thomas Seibert and Martin Kastner had seen the behavior in the wild.

But the year before, the scientists had witnessed the behavior in a lab. While trying to find strategies to stop snakes from reaching nest boxes, the scientists had placed a three-foot-tall, eight-inch-wide stovepipe over the top half of a six-foot-tall metal pole. They fastened a wide platform with two live mice in a cage at the top and placed the contraption in an enclosure with 58 snakes. When reviewing time-lapse footage of the set up taken at night, they saw a snake wrap its tail around the pole, grab the other end of its body to form a secure loop and shimmy up to the top.

“We looked at each other in total shock because this was not anything that we expected or had ever seen,” says Seibert. “We had to watch this over and over just to be sure that we were seeing what we thought we were seeing.”

The unexpected climbing strategy is a unique form of snake locomotion that has never been seen before. The scientists describe the snakes’ movement, which they dub “lasso locomotion,” in a study published today in the journal Current Biology. “I never would have thought in my wildest dreams that a snake would move in this fashion,” says co-author and University of Cincinnati biomechanics specialist Bruce Jayne, who has studied snake locomotion for over 40 years.

The finding provides new insights into why brown tree snakes have been so devastating to birds on Guam, and will help conservationists devise new tools to protect the birds, like Micronesian starlings, that remain.

In order to better understand lasso locomotion, the researchers set up a new experiment in 2019 at the United States Geological Survey’s brown tree snake laboratory in Guam that would encourage the behavior. They swapped the large stovepipe for a smaller, six-inch-diameter stovepipe from Home Depot, and topped the pipe with a cage containing a dead mouse as bait. They placed the pipe in an enclosure housing 15 brown tree snakes.

Five of them latched on and made the climb using lasso locomotion.

Unlike snakes using concertina locomotion, lasso-climbing snakes have only one anchor point, the loop around the cylinder. A slight bend in the lasso moves along the snake’s body, from its head toward its tail, slowly shifting the snake upward and creating its steady ascent.

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/invasive-brown-tree-snakes-stun-scientists-amazing-new-climbing-tactic-180976728/