Ice is melting faster worldwide, with greater sea-level rise anticipated, studies show.

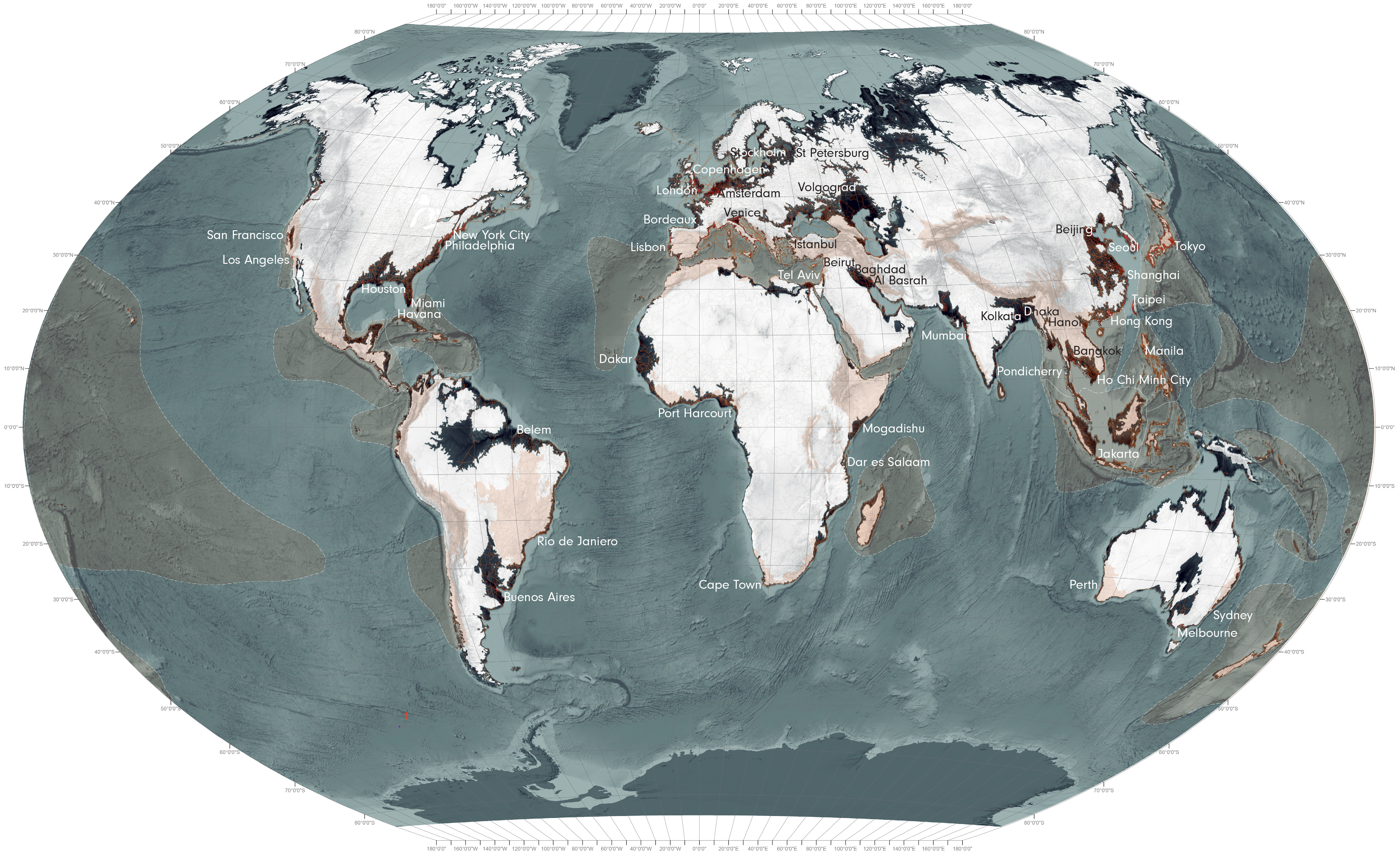

Global ice loss has increased rapidly over the past two decades, and scientists are still underestimating just how much sea levels could rise, according to alarming new research published this month.

From the thin ice shield covering most of the Arctic Ocean to the mile-thick mantle of the polar ice sheets, ice losses have soared from about 760 billion tons per year in the 1990s to more than 1.2 trillion tons per year in the 2010s, a new study released Monday shows. That is an increase of more than 60 percent, equating to 28 trillion tons of melted ice in total — and it means that roughly 3 percent of all the extra energy trapped within Earth’s system by climate change has gone toward turning ice into water.

There is good reason to think the rate of ice melt will continue to accelerate. A second, NASA-backed study on the Greenland ice sheet, for instance, finds that no less than 74 major glaciers that terminate in deep, warming ocean waters are being severely undercut and weakened.

And it asserts that the extent of this effect, along with its implications for rising seas, is still being discounted by the global scientific community.

Failing to fully account for the role of ocean undercutting means sea-level rise from the ice sheets may be underestimated by “at least a factor of 2,” the new paper in the journal Science Advances finds.

The first finds that the current ice losses, which are accelerating quickly, are on pace with the worst scenarios for sea-level rise put out by the United Nation’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). That expert body found that ice sheets could drive as much as 16 inches of sea-level rise by 2100.

But on top of that, the new NASA work on Greenland suggests that the IPCC, whose sea-level projections have long been faulted as being conservative, could underestimate future sea-level rise if the panel, which has a new report expected later this year, does not take full account of the power of the ocean to knock the ice backward and undermine it.

“In these deep fjords, warm water lurks hundreds of feet below the ocean surface, melting the glaciers from below,” Wood said. “When those warm waters become even warmer — a phenomenon we saw through the early 2000s — the melt increases, causing the glaciers to recede, become unstable and lose ice.”

The science produced by the six-year field campaign, known as Oceans Melting Greenland, may force modelers to rethink their estimates for future ice loss, not just in Greenland but also for glaciers where similar dynamics are at work in Antarctica, such as in the West Antarctic ice sheet.

The NASA-led research shows that the undercutting of glaciers by relatively mild ocean waters explains why so many of Greenland’s glaciers have sped their movement into the ocean, adding to sea-level rise, while some others have not accelerated as much.

In many coastal locations, relatively mild, salty waters sit below a layer of colder, fresher water in glacial fjords. These mild waters are coming into contact with the base of glaciers, where ice meets bedrock, which destabilizes the ice.

“A large amount of a glacier’s stability depends on ice at its base,” Wood said. “Remove it and you destabilize the whole thing, like Achilles’ heel.”

At the same time, during the summer months, meltwater from inland areas can flow all the way to the base of glaciers that end in the sea and pour into the fjords. This fresh water can drag some of the heavier, warm water toward the surface, accelerating melting further.

The NASA data shows that the shape of the land undergirding glaciers and the water temperatures in coastal areas help determine the rate of Greenland’s ice loss, but this information isn’t being translated yet into projections for sea-level rise.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/climate-environment/2021/01/25/ice-melt-quickens-greenland-glaciers/?utm_source=pocket-newtab-intl-en