As an aged beginner musician, I thought this was really good:

As an aged beginner musician, I thought this was really good:

what’s the lowdown

SCIENCE said:

what’s the lowdown

It’s a pitch on pitch.

Gave me a better pitcher of how it works.

watching that, cheers

transcript

in typical western music we write all of our music using only 12 unique notes c c sharp d d sharp e f f sharp g g sharp a a sharp and b of course on an instrument like the piano we have far more than 12 keys to play but each of these keys is just a different version of one of those 12 unique pitch classes however like i explored in my previous video on micro tenanity there are actually more than 12 unique pitch classes that we could choose from notes like c half sharp or c half flat in fact pitch is a spectrum with arguably an infinite amount of different notes available so why do we only use these 12 well the first thing to bear in mind here is that these notes weren’t selected for their particular frequencies the frequencies themselves aren’t actually the important thing when it comes to making music for example we could sharpen all of these pictures and as long as we sharpen them all by the same amount the piano will still sound just as harmonious as usual it’s not the frequencies of the notes that are important it’s the intervals between those frequencies a melody isn’t really a sequence of notes but a sequence of intervals twinkle twinkle little star isn’t defined by being these notes or even these frequencies but by being these intervals you can choose any pitch for the first note and then as long as you apply this order of intervals you’ll get twinkle twinkle little star that’s why if we transpose the song to a different key it will still sound like the same song so going back to the initial question why does western music only use 12 notes well put shortly it’s because these 12 notes are the most practical and effective way to play all of the intervals that we find useful for music making so what are these useful intervals and why is 12 notes in an octave the best way to access them even though musical intervals are technically subjective most humans will agree on the same handful of pictures as the most consonant as the most pleasing and musical it’s widely accepted that the octave is the most consonant and most important interval in music notes and octave apart sound so good together so complementary that they are actually perceived as deeper or higher versions of the exact same note this is called octave equivalence and is why notes an octave apart are given the exact same name as each other for example a and a the interval of an octave is also the simplest relationship we can have between the two frequencies to go up an octave all you have to do is double with the frequency so an octave up from 220 hertz is 440 hertz a two to one relationship this also means that a string that is half the length of another will sound exactly an octave higher as it will vibrate twice as fast because notes an octave apart are perceived as different versions of the same note most tuning systems around the world including the western 12 tone system prioritize the octave and then find a way to divide the octave up into different notes the western way of dividing the octave into 12 different notes does a great job of allowing us access to our most important musical intervals so let’s go through those intervals now and add them onto this keyboard the next two most consonant intervals are generally considered to be the perfect fifth and the perfect fourth now of course we’re only really choosing these intervals because they just sound nice to our ears however interestingly just like how the octave had a simple relationship between its two frequencies the perfect fifth and the perfect fourth also have very simple relationships between the two notes to go up an octave we multiplied the frequency by two instead for a perfect fifth we multiply it by one and a half or for a perfect fourth we multiply it by one and a third of course like i said before we’re not consciously choosing these intervals because of these simple relationships but it turns out that the more consonant an interval sounds to us the simpler the relationship between its two notes and this as you would imagine is not a coincidence when two frequencies are related to each other by a simple relationship like two to one the wavelengths of those frequencies are going to perfectly line up perfectly synchronize and it’s generally considered that this perfect alignment of the frequencies is why these intervals are perceived as consonant to us why they’re perceived as harmonious if we play two notes that don’t synchronize together like this you can hear the dissonance the octave the perfect fifth and the perfect fourth are widely considered the most consonant and pleasing intervals after these three though the order in which different people may rank the remaining intervals will start to vary however it would generally follow an order similar to this the major third the minor third the major sixth and the minor sixth and as you may have guessed these intervals once again have simple relationships to the initial note so we now have all of the intervals that are generally considered consonant the remaining intervals offered in the 12 tone western system are considered to be dissonant but this doesn’t mean that they’re not useful to us although dissonance in music seems like something you’d want to avoid music without any dissonance at all may sound pleasant but will lack any drama or suspense it won’t have a sense of tension and release so let’s add these traditionally more dissonant intervals these are the tone or major second the minor seventh the tritone the major seventh [Music] and the semitone or minor second so these are the twelve intervals available to us in the western 12 tone system but why can’t we just add a couple extra pictures in between a few of these for example a neutral third which would be between the major and minor third or we could have a note between the major seventh and the octave creating a sort of ultra seventh or ultra leading tone the thing is though we can’t really just add these two extra micro tonal intervals and leave it at that this is because it’s quite important that the notes between the octave are more or less equally spaced this allows us to easily play in different keys and generally makes the instrument much easier to play with the standard 12 pictures in the octave the notes are naturally spaced at fairly equal distances from each other but if we add just a couple micro tonal notes in like this it will destroy that equal spacing if we’re going to add more notes beyond the standard 12 we will need to find an alternative way to evenly divide up the octave which can still allow us to play all of the most important intervals like the perfect fifth the perfect fourth etc nineteen notes in the octave is a fairly good alternative nineteen evenly spaced notes in the octave still allows us to play our most important intervals like the perfect fifth the perfect fourth etcetera whilst also allowing us to access a whole range of other micro tonal notes another option is to have 24 notes in the octave adding a new microtonal note between each of our standard 12 pictures this of course maintains all of our standard intervals whilst adding a whole range of new micro tonal notes some musicians have written music using systems like these evan wistenkratsky for example developed a quarter tone piano which features 24 notes per octave but as you can see having access to these extra notes makes the instrument significantly more confusing to play even though 19 notes per octave or 24 notes per octave allow us to play a whole range of additional micro toner intervals i think most musicians would agree that these extra micro tonal notes are not useful enough to warrant reducing the playability of our instruments of course some instruments like the violin or the trombone don’t have to be modified to access the notes between the standard 12 but instruments like these are still built to optimize 12 notes in an octave the instrument’s design size and shape are all dictated by making sure the instrument can comfortably access 12 notes in the octave the design of a musical instrument has to strike a compromise between being comfortable and practical to play and having access to as many notes as possible and it turns out that over the centuries we’ve come to this conclusion that 12 notes in an octave repeating up and down the keyboard is the best solution to this compromise 12 notes in an octave is the best way to access the most consonant and useful musical intervals whilst also optimizing the playability of our instruments so that’s it right we’ve found our 12 notes so we can now just double each of those frequencies to give us another set an octave up and we could half them to get another set an octave down and if we do that a couple more times we wind up with the full span of a modern piano jobs are gooden right well not quite there is one more topic left to discuss temperament see right now we’ve tuned our instrument to what’s called just intonation our intervals are tuned to perfect ratios which is ultimately the purest way to tune an interval but even though this is the purest way to tune our intervals it presents a problem do you remember when i mentioned earlier that our notes need to be evenly spaced if we’re going to be able to play in different keys well even though the 12 notes of just intonation are fairly equally distanced from each other they are not perfectly evenly spaced this is because each interval was tuned using a different ratio away from the root for example the fifth between the a and the e is a perfect three to two relationship and this does mean if we play some music in the key of a major it’s going to sound really pure and perfect however if i try playing in a different key e flat major for example things are not going to sound quite as harmonious problem here is even though this perfect fifth between the a and the e was a perfect three to two relationship the perfect fifth between the e flat and the b flat is not when you change the key you are effectively changing the route so unless you’re going to retune your instrument relative to that new route every time you change key other keys are going to just sound out of tune this is really limiting right we want our instrument to be able to sound good in any key not to mention being able to play chromatically outside of the key so how can we fix this well with something called temperament if we want to be able to play in various keys on one instrument and play chromatic music that goes outside of the key we’re going to have to adjust or temper some of these intervals the way in which you adjust these intervals to make the tuning more versatile is called temperament and across history various temperaments have been used which each find their own way of striking a compromise between preserving how these intervals should sound and being able to play in different keys and tonalities the system that we use today which has almost been universally adopted is called twelve tone equal temperament twelve tone equal temperament makes sure that every note is the exact same distance from every other note so in equal temperament a perfect fifth between a and e will sound just as in tune as a perfect fifth between b flat and f or d and a or e and b the way this is achieved is instead of tuning every interval as a perfect ratio we just tuned the octave as a pure ideal ratio and then we divide the space between each octave into 12 equally spaced notes this division does a pretty amazing job of approximating these intervals but of course apart from the octave the intervals in 12 tone equal tempered music are no longer exactly perfect ratios and therefore slightly out of tune some equal tempered intervals are only slightly different from their pure intonation counterparts for example the perfect fifth and the perfect fourth are only 1.96 away from their ideal [Music] tuning however some of these intervals are quite significantly sharper or flatter an equal tempered major third for example is over 13 sharper than it would be in pure intonation you can hear this difference most distinctly in chords if i play a c major chord in our usual twelfth tone equal temperament you’ll hear a wah wah sound because the three pictures of the chord are not perfectly in tune with each other [Music] this wah-wah sound is called beating however if i tune the c major chord to just intonation this beating sound disappears [Music] the thing is though like i mentioned almost every piece of music you’ve ever listened to is in 12 tone equal temperament so although these intervals are slightly out of tune they’re just in tune enough that we don’t really perceive any sort of difference when we listen to our music so hopefully this video has at least in part answered the question of why western music generally uses just 12 notes for such a simple sounding question the answer can actually be quite confusing being a tangle of history physics and human preference and of course you don’t have to stick to just 12 notes micro tonality for example is music that uses notes beyond and between the 12 standard pictures and many non-western cultures around the world use completely different tuning systems i’m actually planning a future video on how different cultures around the world approach tuning and pitch so if you’re trained in the non-western style of music i’d love to hear from you [Music] [Applause] also a big thanks goes to mod art who gifted me a copy of their piano tech software to help me make this video piano tech is a super versatile piano plugin that lets you tune your keyboard to any possible tuning so i thought it would be fitting to wrap this video up with this piano piece that i composed in just intonation [Applause] [Music] [Applause] [Music] [Music] and as always a massive thank you goes to everybody who supports me on patreon including adam granger andrei scientiagia andrew andrew brown andy deacon austin barrett austin russell bob mckinstry britney parker bruce mount cameron all available chris cabell christopher ryan kieran bennen darren harvey d david lee fish david defunder dr darren wicks elena scorchenko espen hansen eugene leroy eyes fd hodor gillamo latona james kao j.a cookensberger joe watson jonas sodastrom justin vigger lavender monroe’s meg fellows melody composers squared michael vivian nancy gillard paul miller paul hazel peter dunphy roger clay sam lin steve daly thomas armstrong tim beaker tim payne toot vidad flowers and vladimir kodakov you

SCIENCE said:

transcriptin typical western music we write all of our music using only 12 unique notes c c sharp d d sharp e f f sharp g g sharp a a sharp and b of course on an instrument like the piano we have far more than 12 keys to play but each of these keys is just a different version of one of those 12 unique pitch classes however like i explored in my previous video on micro tenanity there are actually more than 12 unique pitch classes that we could choose from notes like c half sharp or c half flat in fact pitch is a spectrum with arguably an infinite amount of different notes available so why do we only use these 12 well the first thing to bear in mind here is that these notes weren’t selected for their particular frequencies the frequencies themselves aren’t actually the important thing when it comes to making music for example we could sharpen all of these pictures and as long as we sharpen them all by the same amount the piano will still sound just as harmonious as usual it’s not the frequencies of the notes that are important it’s the intervals between those frequencies a melody isn’t really a sequence of notes but a sequence of intervals twinkle twinkle little star isn’t defined by being these notes or even these frequencies but by being these intervals you can choose any pitch for the first note and then as long as you apply this order of intervals you’ll get twinkle twinkle little star that’s why if we transpose the song to a different key it will still sound like the same song so going back to the initial question why does western music only use 12 notes well put shortly it’s because these 12 notes are the most practical and effective way to play all of the intervals that we find useful for music making so what are these useful intervals and why is 12 notes in an octave the best way to access them even though musical intervals are technically subjective most humans will agree on the same handful of pictures as the most consonant as the most pleasing and musical it’s widely accepted that the octave is the most consonant and most important interval in music notes and octave apart sound so good together so complementary that they are actually perceived as deeper or higher versions of the exact same note this is called octave equivalence and is why notes an octave apart are given the exact same name as each other for example a and a the interval of an octave is also the simplest relationship we can have between the two frequencies to go up an octave all you have to do is double with the frequency so an octave up from 220 hertz is 440 hertz a two to one relationship this also means that a string that is half the length of another will sound exactly an octave higher as it will vibrate twice as fast because notes an octave apart are perceived as different versions of the same note most tuning systems around the world including the western 12 tone system prioritize the octave and then find a way to divide the octave up into different notes the western way of dividing the octave into 12 different notes does a great job of allowing us access to our most important musical intervals so let’s go through those intervals now and add them onto this keyboard the next two most consonant intervals are generally considered to be the perfect fifth and the perfect fourth now of course we’re only really choosing these intervals because they just sound nice to our ears however interestingly just like how the octave had a simple relationship between its two frequencies the perfect fifth and the perfect fourth also have very simple relationships between the two notes to go up an octave we multiplied the frequency by two instead for a perfect fifth we multiply it by one and a half or for a perfect fourth we multiply it by one and a third of course like i said before we’re not consciously choosing these intervals because of these simple relationships but it turns out that the more consonant an interval sounds to us the simpler the relationship between its two notes and this as you would imagine is not a coincidence when two frequencies are related to each other by a simple relationship like two to one the wavelengths of those frequencies are going to perfectly line up perfectly synchronize and it’s generally considered that this perfect alignment of the frequencies is why these intervals are perceived as consonant to us why they’re perceived as harmonious if we play two notes that don’t synchronize together like this you can hear the dissonance the octave the perfect fifth and the perfect fourth are widely considered the most consonant and pleasing intervals after these three though the order in which different people may rank the remaining intervals will start to vary however it would generally follow an order similar to this the major third the minor third the major sixth and the minor sixth and as you may have guessed these intervals once again have simple relationships to the initial note so we now have all of the intervals that are generally considered consonant the remaining intervals offered in the 12 tone western system are considered to be dissonant but this doesn’t mean that they’re not useful to us although dissonance in music seems like something you’d want to avoid music without any dissonance at all may sound pleasant but will lack any drama or suspense it won’t have a sense of tension and release so let’s add these traditionally more dissonant intervals these are the tone or major second the minor seventh the tritone the major seventh [Music] and the semitone or minor second so these are the twelve intervals available to us in the western 12 tone system but why can’t we just add a couple extra pictures in between a few of these for example a neutral third which would be between the major and minor third or we could have a note between the major seventh and the octave creating a sort of ultra seventh or ultra leading tone the thing is though we can’t really just add these two extra micro tonal intervals and leave it at that this is because it’s quite important that the notes between the octave are more or less equally spaced this allows us to easily play in different keys and generally makes the instrument much easier to play with the standard 12 pictures in the octave the notes are naturally spaced at fairly equal distances from each other but if we add just a couple micro tonal notes in like this it will destroy that equal spacing if we’re going to add more notes beyond the standard 12 we will need to find an alternative way to evenly divide up the octave which can still allow us to play all of the most important intervals like the perfect fifth the perfect fourth etc nineteen notes in the octave is a fairly good alternative nineteen evenly spaced notes in the octave still allows us to play our most important intervals like the perfect fifth the perfect fourth etcetera whilst also allowing us to access a whole range of other micro tonal notes another option is to have 24 notes in the octave adding a new microtonal note between each of our standard 12 pictures this of course maintains all of our standard intervals whilst adding a whole range of new micro tonal notes some musicians have written music using systems like these evan wistenkratsky for example developed a quarter tone piano which features 24 notes per octave but as you can see having access to these extra notes makes the instrument significantly more confusing to play even though 19 notes per octave or 24 notes per octave allow us to play a whole range of additional micro toner intervals i think most musicians would agree that these extra micro tonal notes are not useful enough to warrant reducing the playability of our instruments of course some instruments like the violin or the trombone don’t have to be modified to access the notes between the standard 12 but instruments like these are still built to optimize 12 notes in an octave the instrument’s design size and shape are all dictated by making sure the instrument can comfortably access 12 notes in the octave the design of a musical instrument has to strike a compromise between being comfortable and practical to play and having access to as many notes as possible and it turns out that over the centuries we’ve come to this conclusion that 12 notes in an octave repeating up and down the keyboard is the best solution to this compromise 12 notes in an octave is the best way to access the most consonant and useful musical intervals whilst also optimizing the playability of our instruments so that’s it right we’ve found our 12 notes so we can now just double each of those frequencies to give us another set an octave up and we could half them to get another set an octave down and if we do that a couple more times we wind up with the full span of a modern piano jobs are gooden right well not quite there is one more topic left to discuss temperament see right now we’ve tuned our instrument to what’s called just intonation our intervals are tuned to perfect ratios which is ultimately the purest way to tune an interval but even though this is the purest way to tune our intervals it presents a problem do you remember when i mentioned earlier that our notes need to be evenly spaced if we’re going to be able to play in different keys well even though the 12 notes of just intonation are fairly equally distanced from each other they are not perfectly evenly spaced this is because each interval was tuned using a different ratio away from the root for example the fifth between the a and the e is a perfect three to two relationship and this does mean if we play some music in the key of a major it’s going to sound really pure and perfect however if i try playing in a different key e flat major for example things are not going to sound quite as harmonious problem here is even though this perfect fifth between the a and the e was a perfect three to two relationship the perfect fifth between the e flat and the b flat is not when you change the key you are effectively changing the route so unless you’re going to retune your instrument relative to that new route every time you change key other keys are going to just sound out of tune this is really limiting right we want our instrument to be able to sound good in any key not to mention being able to play chromatically outside of the key so how can we fix this well with something called temperament if we want to be able to play in various keys on one instrument and play chromatic music that goes outside of the key we’re going to have to adjust or temper some of these intervals the way in which you adjust these intervals to make the tuning more versatile is called temperament and across history various temperaments have been used which each find their own way of striking a compromise between preserving how these intervals should sound and being able to play in different keys and tonalities the system that we use today which has almost been universally adopted is called twelve tone equal temperament twelve tone equal temperament makes sure that every note is the exact same distance from every other note so in equal temperament a perfect fifth between a and e will sound just as in tune as a perfect fifth between b flat and f or d and a or e and b the way this is achieved is instead of tuning every interval as a perfect ratio we just tuned the octave as a pure ideal ratio and then we divide the space between each octave into 12 equally spaced notes this division does a pretty amazing job of approximating these intervals but of course apart from the octave the intervals in 12 tone equal tempered music are no longer exactly perfect ratios and therefore slightly out of tune some equal tempered intervals are only slightly different from their pure intonation counterparts for example the perfect fifth and the perfect fourth are only 1.96 away from their ideal [Music] tuning however some of these intervals are quite significantly sharper or flatter an equal tempered major third for example is over 13 sharper than it would be in pure intonation you can hear this difference most distinctly in chords if i play a c major chord in our usual twelfth tone equal temperament you’ll hear a wah wah sound because the three pictures of the chord are not perfectly in tune with each other [Music] this wah-wah sound is called beating however if i tune the c major chord to just intonation this beating sound disappears [Music] the thing is though like i mentioned almost every piece of music you’ve ever listened to is in 12 tone equal temperament so although these intervals are slightly out of tune they’re just in tune enough that we don’t really perceive any sort of difference when we listen to our music so hopefully this video has at least in part answered the question of why western music generally uses just 12 notes for such a simple sounding question the answer can actually be quite confusing being a tangle of history physics and human preference and of course you don’t have to stick to just 12 notes micro tonality for example is music that uses notes beyond and between the 12 standard pictures and many non-western cultures around the world use completely different tuning systems i’m actually planning a future video on how different cultures around the world approach tuning and pitch so if you’re trained in the non-western style of music i’d love to hear from you [Music] [Applause] also a big thanks goes to mod art who gifted me a copy of their piano tech software to help me make this video piano tech is a super versatile piano plugin that lets you tune your keyboard to any possible tuning so i thought it would be fitting to wrap this video up with this piano piece that i composed in just intonation [Applause] [Music] [Applause] [Music] [Music] and as always a massive thank you goes to everybody who supports me on patreon including adam granger andrei scientiagia andrew andrew brown andy deacon austin barrett austin russell bob mckinstry britney parker bruce mount cameron all available chris cabell christopher ryan kieran bennen darren harvey d david lee fish david defunder dr darren wicks elena scorchenko espen hansen eugene leroy eyes fd hodor gillamo latona james kao j.a cookensberger joe watson jonas sodastrom justin vigger lavender monroe’s meg fellows melody composers squared michael vivian nancy gillard paul miller paul hazel peter dunphy roger clay sam lin steve daly thomas armstrong tim beaker tim payne toot vidad flowers and vladimir kodakov you

Why does the author use zero punctuation?

Tamb said:

SCIENCE said:

transcript…

Why does the author use zero punctuation?

English (auto-generated)

SCIENCE said:

Tamb said:

SCIENCE said:

transcript…

Why does the author use zero punctuation?

English (auto-generated)

(Laughs in quarter tones)

Poor Johnny one note, yelled willy nilly

Cymek said:

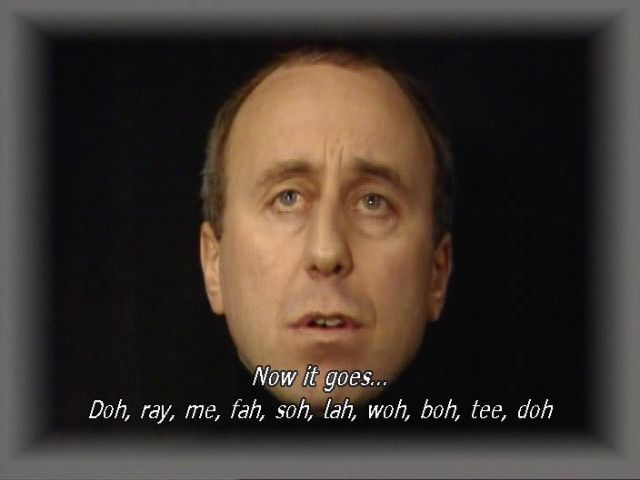

So Bing tells me this is something to do with Red Dwarf.

But ISDGI

The Rev Dodgson said:

Cymek said:

So Bing tells me this is something to do with Red Dwarf.

But ISDGI

Holly decided to invent a decimal musical note system.

party_pants said:

The Rev Dodgson said:

Cymek said:

So Bing tells me this is something to do with Red Dwarf.

But ISDGI

Holly decided to invent a decimal musical note system.

d’oh

I should have got that :)

party_pants said:

The Rev Dodgson said:

Cymek said:

So Bing tells me this is something to do with Red Dwarf.

But ISDGI

Holly decided to invent a decimal musical note system.

I tried it out in real life – and it works!

Normally, we have frequencies mapped to notes on a logarithmic scale.

But I found I could make a workable decimal musical note system by mapping frequencies to notes using a linear scale.

And the result would be similar in pitch to Holly’s singing, with lower notes of the C scale (C,D,E/E-flat,F) being almost equidistant in the decimal system, but then extra notes slotting in between the standard pitches higher in the scle. This is better than the standard system where a normal scale consistes of intervals varying between adjacent notes of the scale. The decimal musical scale resets every decade to twice the intervals of the decade further down. Which is just simply the mapping from semitones to whole tones that we use all the time in music.

All I need now is a musical instrument that can be tuned to a decimal scale. The violin would be a good start because each string can be tuned separately to any pitch and the finger position along the string can be any pitch. So it is theoretically possible to play Holly’s decimal music system on a violin.

In case you think that that’s ridiculous, the native music of Georgia (former USSR) does not use octave jumps, an octive is considered a dissonant interval. Which is even weirder than Holly’s proposal.

mollwollfumble said:

party_pants said:

The Rev Dodgson said:So Bing tells me this is something to do with Red Dwarf.

But ISDGI

Holly decided to invent a decimal musical note system.

I tried it out in real life – and it works!

Normally, we have frequencies mapped to notes on a logarithmic scale.

But I found I could make a workable decimal musical note system by mapping frequencies to notes using a linear scale.And the result would be similar in pitch to Holly’s singing, with lower notes of the C scale (C,D,E/E-flat,F) being almost equidistant in the decimal system, but then extra notes slotting in between the standard pitches higher in the scle. This is better than the standard system where a normal scale consistes of intervals varying between adjacent notes of the scale. The decimal musical scale resets every decade to twice the intervals of the decade further down. Which is just simply the mapping from semitones to whole tones that we use all the time in music.

All I need now is a musical instrument that can be tuned to a decimal scale. The violin would be a good start because each string can be tuned separately to any pitch and the finger position along the string can be any pitch. So it is theoretically possible to play Holly’s decimal music system on a violin.

In case you think that that’s ridiculous, the native music of Georgia (former USSR) does not use octave jumps, an octive is considered a dissonant interval. Which is even weirder than Holly’s proposal.

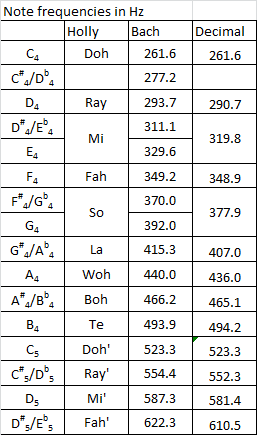

Perhaps I can explain Holly’s decimal music system more simply.

You know the melodic minor scale: C, D, Eflat, F, G, Aflat, A, Bflat, B and back to C.

where A and B are used on the way up but Aflat and Bflat are used on the way down.

Retain all 10 notes.

Doh = C, Ray = D, Mi = Eflat, Fah = F, So = G,

La = Aflat, Woh = A, Boh = Bflat, Te = B, Doh = C

But instead of sticking rigidly to tome/semitone intervals, even the intervals out so that each interval is exactly the same size in linear (not logarithmic) frequency.

mollwollfumble said:

Perhaps I can explain Holly’s decimal music system more simply.You know the melodic minor scale: C, D, Eflat, F, G, Aflat, A, Bflat, B and back to C.

where A and B are used on the way up but Aflat and Bflat are used on the way down.

Retain all 10 notes.

Scratches head.

I really must try and get into these major and minor scale things some time.

At the moment I can find the right note if it’s marked #, but that’s about it.

The Rev Dodgson said:

mollwollfumble said:

Perhaps I can explain Holly’s decimal music system more simply.You know the melodic minor scale: C, D, Eflat, F, G, Aflat, A, Bflat, B and back to C.

where A and B are used on the way up but Aflat and Bflat are used on the way down.

Retain all 10 notes.Scratches head.

I really must try and get into these major and minor scale things some time.

At the moment I can find the right note if it’s marked #, but that’s about it.

C, D, Eflat, F, G, Aflat, A, Bflat, B and back to C

when marked # is

C, D, D#, F, G, G#, A, A#, B and back to C

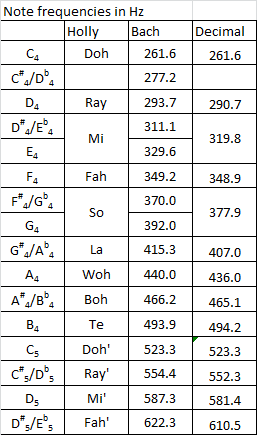

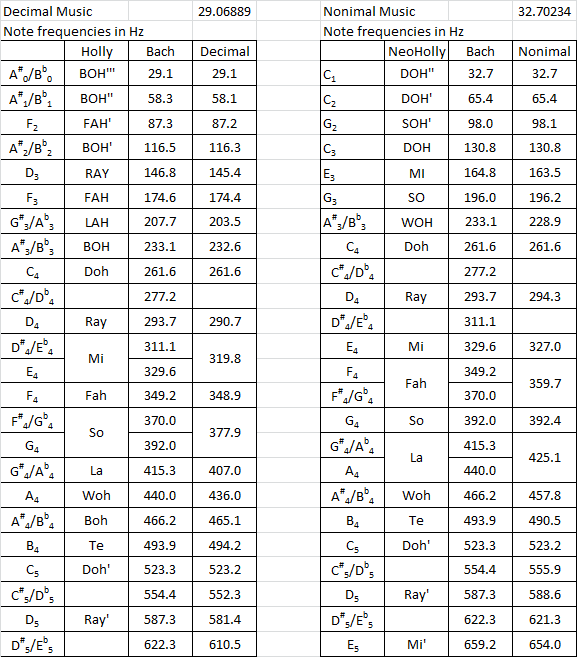

Comparison of Bach’s “Even Tempered” scale with Holly’s decimal scale.

I want you to note in paricular how Holly’s “Mi” lies intermediate in frequency between the notes in the major and minor scale, so unifying the major and minor to make music simpler and more melodious. Take that, Bach!

mollwollfumble said:

The Rev Dodgson said:

mollwollfumble said:

Perhaps I can explain Holly’s decimal music system more simply.You know the melodic minor scale: C, D, Eflat, F, G, Aflat, A, Bflat, B and back to C.

where A and B are used on the way up but Aflat and Bflat are used on the way down.

Retain all 10 notes.Scratches head.

I really must try and get into these major and minor scale things some time.

At the moment I can find the right note if it’s marked #, but that’s about it.

C, D, Eflat, F, G, Aflat, A, Bflat, B and back to C

when marked # is

C, D, D#, F, G, G#, A, A#, B and back to CComparison of Bach’s “Even Tempered” scale with Holly’s decimal scale.

I want you to note in paricular how Holly’s “Mi” lies intermediate in frequency between the notes in the major and minor scale, so unifying the major and minor to make music simpler and more melodious. Take that, Bach!

I need to add two caveats here.

One is that Holly’s decimalised music is not suited to “transposition” in the normal sense. In transposition in the normal sense, the frequency is changed logarithmically during the transposition. But frequency isn’t counted logarithmically in the decimalised music.

However, and here’s a big plus, Holly’s decimalised music is suited to the use of modes from Greek music better than Bach’s even tempered scale. By ‘modes’ I mean Ionian, Dorian, Phrygian, Lydian, Mixolydian, Aeolian and Locrian modes, etc. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mode_

mollwollfumble said:

mollwollfumble said:

The Rev Dodgson said:Scratches head.

I really must try and get into these major and minor scale things some time.

At the moment I can find the right note if it’s marked #, but that’s about it.

C, D, Eflat, F, G, Aflat, A, Bflat, B and back to C

when marked # is

C, D, D#, F, G, G#, A, A#, B and back to CComparison of Bach’s “Even Tempered” scale with Holly’s decimal scale.

I want you to note in paricular how Holly’s “Mi” lies intermediate in frequency between the notes in the major and minor scale, so unifying the major and minor to make music simpler and more melodious. Take that, Bach!

I need to add two caveats here.

One is that Holly’s decimalised music is not suited to “transposition” in the normal sense. In transposition in the normal sense, the frequency is changed logarithmically during the transposition. But frequency isn’t counted logarithmically in the decimalised music.

However, and here’s a big plus, Holly’s decimalised music is suited to the use of modes from Greek music better than Bach’s even tempered scale. By ‘modes’ I mean Ionian, Dorian, Phrygian, Lydian, Mixolydian, Aeolian and Locrian modes, etc. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mode_

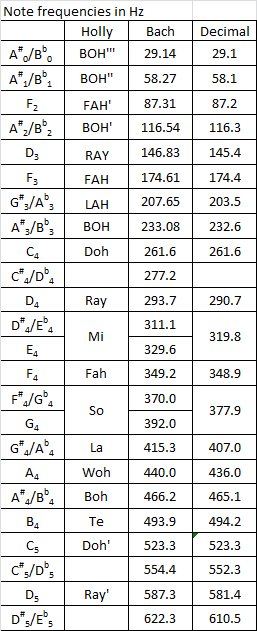

When I extend Holly’s Decimal music scale downwards in pitch, I get a remarkably good match in frequencies to Bach’s even-tempered scale.

Another advantage is that the Decimal music scale starts with an octave jump in the bass, which is how music harmony is normally played anyway. Followed upwards by an arpeggio, which again is how music harmony is usually played.Consider the start of Fur Elise for example.

The shocker, though, is that when Holly’s scale is extended downwards, the lowest not is not octaves below Doh but octaves below Boh. So, really, Holly’s scale becomes BOH Doh Ray Mi Fas So Lah Woh Boh, which has nine notes rather than ten as Te is missing in the primary octave.

That is equivalent to a modal scale. Which one?

Extending Holly’s Decmal music scale downwards in pitch:

Decimal music and Nonimal music.

I would love to know what these scales sound like.

mollwollfumble said:

Decimal music and Nonimal music.

I would love to know what these scales sound like.

“Constructing scales from scratch is one of Scala’s strengths. Kinds of scales that can be made with Scala include: equal temperaments, well-temperaments, Pythagorean (meantone) scales, Euler-Fokker genera, Fokker periodicity blocks, harmonic scales, Partch diamonds, Polychordal scales, Dwarf scales and Wilson Combination Product Sets. In addition, a set of command files is included to build other kinds of scales such as triadic scales, circular mirrorings, circulating temperaments, etc.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Microtonal_music

“Microtonal music or microtonality is the use in music of microtones—intervals smaller than a semitone, also called “microintervals”. It may also be extended to include any music using intervals not found in the customary Western tuning of twelve equal intervals per octave. In other words, a microtone may be thought of as a note that falls between the keys of a piano tuned in equal temperament.”

“Electronic music facilitates the use of any kind of microtonal tuning, and sidesteps the need to develop new notational systems. In 1954, Karlheinz Stockhausen built his electronic Studie II on an 81-step scale starting from 100 Hz with the interval of 51/25 between steps, and in Gesang der Jünglinge (1955–56) he used various scales, ranging from seven up to sixty equal divisions of the octave. In 1955, Ernst Krenek used 13 equal-tempered intervals per octave in his Whitsun oratorio, Spiritus intelligentiae, sanctus”.

“HOBBIT

“HOBBIT scale-size octave

“Create a Just Intonation hobbit scale with the given number of tones and formal octave

“Non-equal temperaments: S5, P7, P5, A17, P17, T17, I22, T24, V31, YA31, A34, A34N, YA36, T48N, EITZ, JI, JI2, SAJI1, SAJI2, SAJI3, SAJI4, SAHTT.

“S5 gives the Central-Javanese note names for slendro.

“P7 gives Central-Javanese note names for pelog.

“P5 gives West-Javanese note names for pelog. …

“ The notation YA36 by Ozan Yarman for Turkish makam music has the following symbols:

| quartertone sharp

d one comma flat

< bakiye (limma) sharp

b- quartertone flat

I think I may have found out how to play the Holly decimal music scale and the neoHolly nonimal music scale. Using SCALA software.

But not how to play tunes on either.

> I think I may have found out how to play the Holly decimal music scale and the neoHolly nonimal music scale. Using SCALA software. But not how to play tunes on either.

Fingers crossed. When mrs m wakes up, I may be able to play tunes using Holly’s decimalised music.

SCALA software includes a weird-looking onscreen digital keyboard. All of Holly’s notes have to be played on the black notes, for some strange reason.

Here’s my take on Holly’s decimalised music.

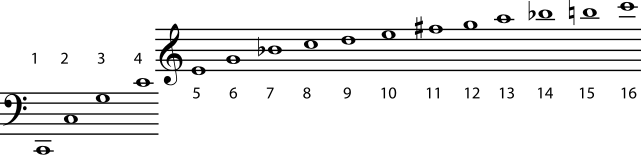

In the main octave it has 9 different notes and in the octave above it has 18 different notes.

This is what the decimalised music scale sounds like.

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1iSuCrg-ybhttRNiQByH-bzqvQ2xz9A8i/view?usp=sharing

I can get an exact number of octaves down the scale if I have 1 note in the lowest octave ©, 2 notes in the second lowest octave (C G), 4 notes in the next lowest octave (C E G Woh), 8 notes in the main octave (the tones) and 16 notes in the octave above the main octave (the semitones).

This is what the nonimalised music scale sounds like. The bottom note has a higher pitch, but the two scales have the same top pitch.

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1bfRNhsvhJrtWOMbgY335tpx2bjSnEvG0/view?usp=sharing

mollwollfumble said:

Here’s my take on Holly’s decimalised music.In the main octave it has 9 different notes and in the octave above it has 18 different notes.

This is what the decimalised music scale sounds like.

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1iSuCrg-ybhttRNiQByH-bzqvQ2xz9A8i/view?usp=sharing

I can get an exact number of octaves down the scale if I have 1 note in the lowest octave ©, 2 notes in the second lowest octave (C G), 4 notes in the next lowest octave (C E G Woh), 8 notes in the main octave (the tones) and 16 notes in the octave above the main octave (the semitones).

This is what the nonimalised music scale sounds like. The bottom note has a higher pitch, but the two scales have the same top pitch.

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1bfRNhsvhJrtWOMbgY335tpx2bjSnEvG0/view?usp=sharing

And here’s the nonimal scale in C again, where I’ve split it into two parts. .mp3 file again.

The bottom part is the apreggio

The top part is the tones in the first octave and the semitones in the second octave

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1iekCuJW6a8kxSDuzBbC9D7LDv5SmWYbH/view?usp=sharing

Found it. :-)

What I’m using is known as the “harmonic series”. It’s so obvious that I thought it had to be well known. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harmonic_series_

“An illustration in musical notation of the harmonic series (on C) up to the 20th harmonic. The numbers above the harmonic indicate the difference – in cents – from equal temperament (rounded to the nearest integer). Blue notes are very flat and red notes are very sharp.”

Note how, from position 16, C D E F G Aflat Bflat B C form a scale octave of 9 tones instead of the more familiar 8 tones. Changing that Gflat to an F, you’ll notice that only 2 notes (the F and Aflat) are significatly off pitch relative to the equal temperement system of semitones.

mollwollfumble said:

Found it. :-)What I’m using is known as the “harmonic series”. It’s so obvious that I thought it had to be well known. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harmonic_series_

“An illustration in musical notation of the harmonic series (on C) up to the 20th harmonic. The numbers above the harmonic indicate the difference – in cents – from equal temperament (rounded to the nearest integer). Blue notes are very flat and red notes are very sharp.”

Note how, from position 16, C D E F G Aflat Bflat B C form a scale octave of 9 tones instead of the more familiar 8 tones. Changing that Gflat to an F, you’ll notice that only 2 notes (the F and Aflat) are significatly off pitch relative to the equal temperement system of semitones.

Hold on, everyone. Harmonic series. So Holly’s decimalised music can be played on a bugle? Yes.

It seldom is because the bugle seldom plays above the bottom 8 notes. But the harmonics from notes 9 to 18 form Holly’s decimalised music scale. The harmonics from notes 8 to 16 of the bugle form the nonimalised music scale.

“Although limited by the fact that it can only play one harmonic series, the bugle can still play many well-known tunes.”