This tooth lay buried in a cave for around 150,000 years until it was brought to light in 2019.

A single ancient tooth found in a Laos cave may be the first physical evidence of an extinct, enigmatic group of humans called Denisovans in South-East Asia.

The molar is unveiled in a study published in Nature Communications today by an international team, which concluded it once belonged to a young girl who lived as far back as 164,000 years ago.

And if added to the Denisovan catalogue, this would be just the third site in the world for such fossils — and one that’s thousands of kilometres south of the others.

“When it was found, I wasn’t surprised, but I was definitely excited,” said study co-author Kira Westaway, a geochronologist at Macquarie University.

Traces of dalliances with Denisovans have been found in the genome of present-day populations, particularly in people indigenous to Australia, Papua New Guinea and some Pacific Islands, and, to a lesser extent, mainland South-East Asia.

“So we knew that there was some intermixing, some integration, in this area,” Dr Westaway said.

Yet despite this, scarcely any Denisovan fossils have been identified — not just in South-East Asia, but anywhere full stop.

So far, there’s a pinky finger bone and a few teeth from Denisova Cave in Russia, plus a jaw bone and a few teeth from Baishiya Cave on the Tibetan Plateau.

A bone from a child with a Neanderthal mother and Denisovan father was recently reported too.

The Laos tooth — found in the tropics — showed how adaptable these ancient humans were, Dr Westaway said.

“If you look at the time range , Denisovans were freezing their arses off in Russia, they were adapting to high altitudes in Tibet, and they were living in balmy tropical caves of Laos all at the same time, but doing it 100,000 years earlier than modern humans were doing it.”

The tale a tooth can tell

So who did the molar — the first or second tooth from the back of a lower left jaw — belong to?

Archaeologists were clued in on the age of the tooth’s owner by its pristineness. It was an adult or permanent tooth, but had no signs of wear and tear, suggesting it hadn’t yet grown through the gum and into the mouth when its owner died.

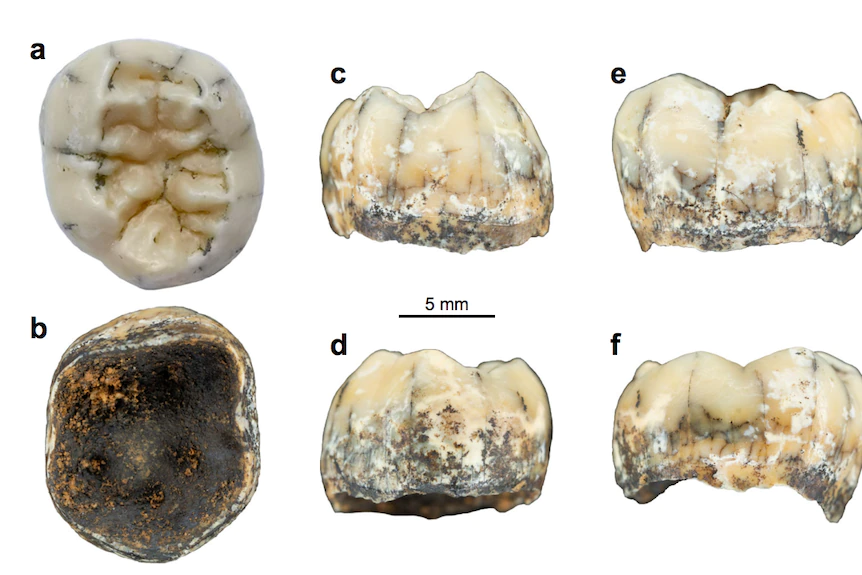

Top, bottom and side views of the tooth discovered in Tam Ngu Hao 2

In the absence of usable DNA — the heat and humidity of the tropics degrades genetic material quickly — they analysed more robust proteins in the tooth enamel to ascertain if it belonged to a boy or girl.

Males produce a particular form of a protein that’s involved in enamel production. The molar did not contain that protein type.

This all pointed to a girl, who was between 3.5 and 8.5 years old when she died.

Now — what type of human was she?

Our species Homo sapiens might be the only type of human knocking around the planet today, but we know quite a few branches of our family tree have, at some point (or points), called South-East Asia home.

The team compared lumps and bumps on the tooth’s surface and under the enamel with other teeth of a range of different humans — including Neanderthals, Homo erectus, Denisovans and Homo sapiens — to rule them out (or in).

For instance, the chewing surface of the tooth was exceptionally crinkled, so much so it couldn’t be H. sapiens, which has a smoother surface.

Teeth previously discovered in Denisova Cave helped in the identification process, said study co-author Renaud Joannes-Boyau, a geochemist at Southern Cross University.

But overall, the tooth looked remarkably similar to its counterpart attached to what many believe is a Denisovan jawbone found in a cave in Tibet.

There were also some similarities to Neanderthal teeth, Dr Joannes-Boyau said, but that was expected.

“We know Denisovans were very, very close to Neanderthals, and we actually believe that Denisovans were once probably a geographically of Neanderthals, but it’s not really clear yet.”