dv said:

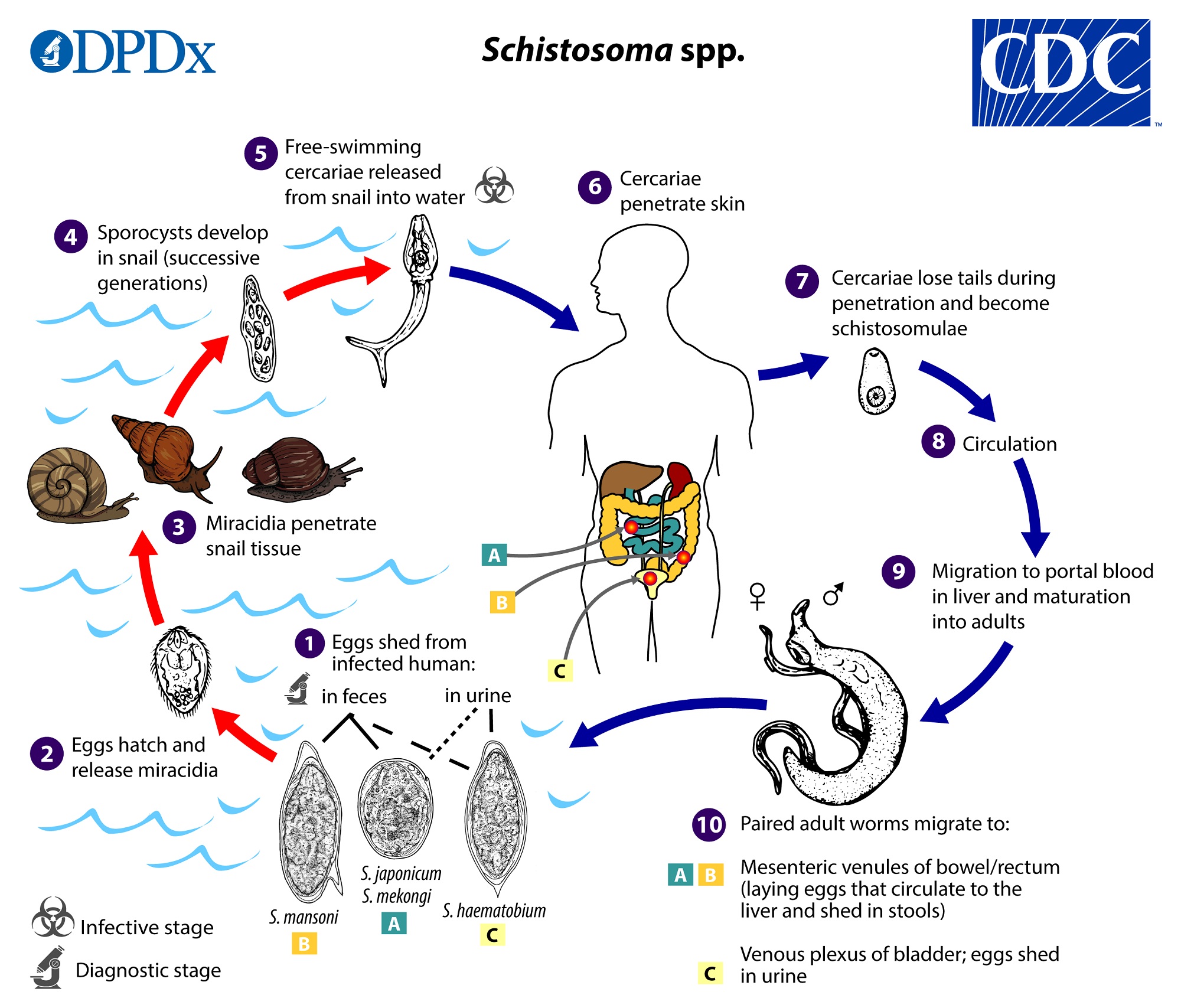

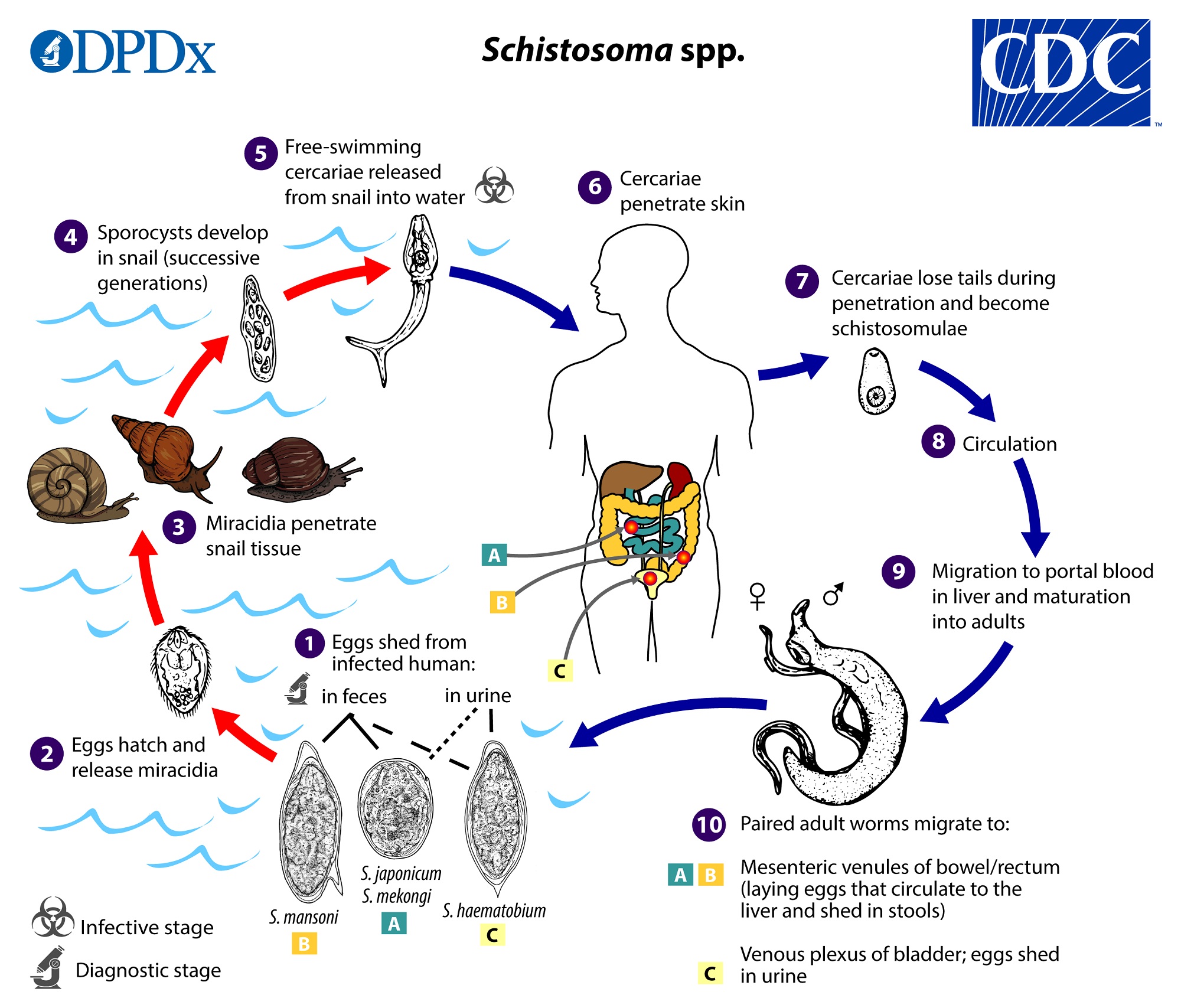

Here’s a life cycle chart from the CDC. Seems it also lays eggs in the venous complex of the bladder so that eggs can get out via the urine, so that’s nice.

I wonder. I had thought that the life cycle of parasitic flukes was:

human feces to eggs to molluscs such as water snails then free-living trematodes in water, then boring into fish, then the human eats the fish.

So where is the fish in the above cycle? Perhaps I have the wrong species of parasitic flukes.

Check https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trematoda

“trematodes have a complex life cycle with at least two hosts. The primary host, where the flukes sexually reproduce, is a vertebrate. The intermediate host, in which asexual reproduction occurs, is usually a snail.”

“The smaller Aspidogastrea, comprising about 100 species, are obligate parasites of mollusks and may also infect turtles and fish, including cartilaginous fish. The Digenea, the majority of trematodes, are obligate parasites of both mollusks and vertebrates, but rarely occur in cartilaginous fish.”

I’ve got it now. Sort of. Check https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Digenea

“There is a bewildering array of variation on the complex digenean life cycle, and plasticity in this trait is probably a key to the group’s success. In general, the life cycles may have two, three, or four obligate (necessary) hosts, sometimes with transport or paratenic hosts in between. The three-host life cycle is probably the most common. In almost all species, the first host in the life cycle is a mollusc. This has led to the inference that the ancestral digenean was a mollusc parasite and that vertebrate hosts were added subsequently.

“Free-swimming cercariae leave the snail host and move through the aquatic or marine environment, often using a whip-like tail, though a tremendous diversity of tail morphology is seen. Cercariae are infective to the second host in the life cycle, and infection may occur passively (e.g., a fish consumes a cercaria) or actively (the cercaria penetrates the fish).

“The life cycles of some digeneans include only two hosts, the second being a vertebrate. In these groups, sexual maturity occurs after the cercaria penetrates the second host, which is in this case also the definitive host. Two-host life cycles can be primary (there never was a third host) as in the Bivesiculidae, or secondary (there was at one time in evolutionary history a third host but it has been lost).

“In three-host life cycles, cercariae develop in the second intermediate host into a resting stage, the metacercaria, which is usually encysted in a cyst of host and parasite origin, or encapsulated in a layer of tissue derived from the host only. This stage is infective to the definitive host. Transmission occurs when the definitive host preys upon an infected second intermediate host.”

“Bilhart’s wrote a paper in 1856 describing the worms more fully and he named them Distoma haematobium. Their unusual morphology meant that they could not be comfortably included in Distoma so in 1856 Meckel von Helmsback created the genus Bilharzia for them. In 1858 Weinland proposed the name Schistosoma after the male worms’ morphology. Despite Bilharzia having precedence the genus name Schistosoma was officially adopted by the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature.”

“An outline of the evolution of the schistosoma is now possible. The ancestral species infected freshwater turtles and the life cycle included gastropod hosts. Some of these species in their turn infected the marine turtles. At some point members of species infecting marine turtles developed the ability to infect birds – most likely waterfowl. This probably occurred somewhere in the Asian continent presumably at or near the coast. The bird species eventually developed the ability to infect mammals. This last development seems to have occurred in Gondwana between 120 million years ago and 70 million years ago.”