Inside the revolutionary jet design that aims to change air travel forever

By Greg Dickinson

July 10, 2025 — 5.00am

Some 101 years after the world’s first “blended-wing body” aircraft took flight (before promptly crashing back down to earth), a flurry of major manufacturers are designing planes in the unique aerodynamic style. This week, we gained a fresh look into how one of these planes might take shape.

The aviation start-up Natilus has published rendered images of its blended-wing body aircraft, a design concept which would allow for more spacious, fuel-efficient and potentially cheaper flights.

The Horizon aircraft will have a range of 3500 nautical miles (6482 kilometres) with a capacity of up to 196 passengers.

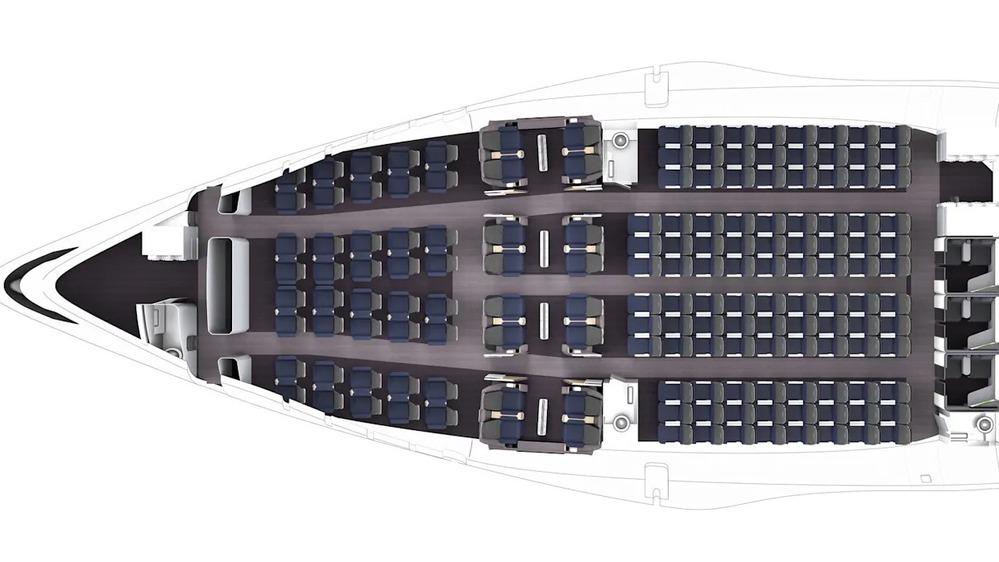

Natilus is a San Diego-based startup, co-founded in 2016 by aircraft design engineers Aleksey Matyushev and Anatoly Starikov. The mock-ups show a seating configuration that would see three aisles running through the plane, with futuristic booths allowing for in-flight video conferencing.

Aviators have theorised over the potential for a blended-wing body (BWB) jet for more than a century. But in recent years, with a sharpened onus on lowering emissions, airline manufacturers including Airbus, Bombardier and Boeing – plus a suite of start-ups – have begun exploring options for blended-wing designs.

A revolutionary design

In simple terms, a BWB aircraft has no clear dividing line between the main body and the wings, which are instead smoothly blended together. The result is an aerodynamic shape, which allows for a more fuel-efficient flight.

The blended wing differs from the “flying wing” – the design used for the B-2 Bomber – which sees an aircraft’s entire payload within the wing structure. But they are similar, in that they are both tailless.

The idea of the BWB was first dreamt up in the 1920s by Russian inventor Nicolas Woyevodsky. The result of his designs was the Westland Dreadnought, a single-engined fixed-winged monoplane. Only one was built, and it crashed on its maiden flight in Yeovil, Somerset, in May 1924, badly injuring the test pilot in the process.

Other prototypes were developed in the decades that followed, including designs by Vincent Burnelli, British manufacturer Miles, and a long-range interceptor aircraft called the “Moonbat”. The latter was designed for the US Air Force, but its production was cancelled after the prototype was destroyed by an engine fire.

Video pods and ‘club seating’

As the decades passed, the BWB design was sidelined in preference of the “tube and wing” design which Boeing and Airbus have adopted. But now, with airlines under pressure to meet net zero targets by 2050, the fuel-efficient BWB aircraft is back on the table.

Natilus is one of the smaller firms in the mix. Its Horizon aircraft will have a range of 3500 nautical miles (6482 kilometres) with a capacity of up to 196 passengers. This puts this particular BWB in a similar playing field to the Boeing 737-800, which has a capacity of 189 seats and a range of 2500 to 3850 nautical miles (4630 to 7130 kilometres).

But it is the other numbers that will catch the attention of prospective buyers. According to Natilus, the Horizon will reduce operating costs by 50 per cent, and the aircraft is 25 per cent lighter than conventional jets.

Natilus says: “Blended-wing bodyaircraft outperform traditional tube-and-wing aircraft in the areas of efficiency, performance, and environmental impact, resulting in improved fleet operations while protecting our planet for future generations.”

At a configuration of 196 passengers, the Horizon would have space for 108 in economy class (at 31-inch pitch), 48 in economy-plus (34 inches or 86cm) and 40 in first class (38 inches or 97cm). Natilus renderings show the potential for “video conference pods”, while there are also plans for “club seating” configurations which would allow groups to sit together during longer flights.

Crucially for prospective buyers, Natilus says its planes are being designed in a way that they can use existing airport infrastructure, plus they will use the same engines as conventional aircraft. In a 2024 interview with CNN, co-founder Matyushev said the plan is for the Horizon to go into service in the early 2030s. It appears that another manufacturer might beat them to it.

Ambitious competitors

California-based startup JetZero has similar ambitions to Natilus. The firm has received the backing of United Airlines, which has pre-ordered 200 of its 250-passenger Z4 plane (which is, as yet, uncertified), which it hopes to launch by 2030. At this size, the aircraft would be bigger than the single-aisle Boeing 737 and Airbus A320, but smaller than their twin-aisle designs, allowing it to fill a vital gap in the market.

The managing director of United Airlines’s Venture has previously said the Z4’s width would create a “living room in the sky”. But it is not only focusing on producing commercial jets. JetZero received a further boost when the US Air Force put in a $US235 million ($A360 million) contract for a demonstrator aircraft. This, according to Frank Kendall, the US secretary of the air force, was all about “maintaining our edge over China”. It could be that these military aircraft are developed first, paving the way for the commercial jets in the future.

Other manufacturers are involved in the race. JetZero traces its origins to a Nasa-McDonnell Douglas project in the early 1990s, which culminated in a successful test-flight of a 17ft demonstrator in 1997 (the JetZero co-founder, Mark Page, led this project). Boeing went on to take on the designs after merging with McDonnell, creating the unmanned X-48B and X48-C aircraft, which were tested more than 100 times. But, ultimately, these were never put into service, as other research initiatives took precedence.

Airbus has revealed plans for a BWB prototype called Maveric, showcased at a Singapore air show in 2020. While Bombardier is the first business jet manufacturer to explore the potential of the blended-wing design with its “EcoJet” project.

The benefits, analysed

Despite Boeing pausing its plans, the blended-wing dream remains alive. Fuel efficiency is the chief reason. Blended-wing jets are considerably more efficient compared with tube-and-wing aircraft, because they can generate more lift at take-off and face less drag as they fly. This means the aircraft is cheaper to run and produces lower emissions.

“They do offer significant fuel savings over conventional aircraft, at least in theory, as they avoid all the common joints and fillets that create form drag, or the loss of energy from wind resistance,” says pilot Brian Smith, who flies for a British cargo airline and has previously flown with Ryanair, Emirates and Air2000 (later, First Choice).

Natilus says its planes are being designed in a way that they can use existing airport infrastructure.

From a passenger point of view, there will be exciting bonuses. The interior would be wider and more spacious, given that the plane is not structured around a long, thin tube. This could allow for some game-changing configurations, impossible in a tubular design. Given that the wider cabin design allows for multiple aisles, the boarding and disembarkation process would likely be much quicker and more pleasant for passengers, too.

By all accounts, BWB aircraft could be quieter than traditional jets. Because they are more aerodynamically efficient, they will be able to use smaller engines that generate less noise. The location of the engines above the fuselage would also shield passengers from excessive noise. Natilus estimates that its planes would be around 40 per cent quieter than tube-and-wing aircraft.

The interior would be wider and more spacious, given that the plane is not structured around a long, thin tube.

And if, as Natilus suggests, the aircraft can run with 50 per cent lower operating costs, this could also allow airlines flying BWB aircraft to be priced more competitively than traditional tube-and-wing services.

Dilemmas and hurdles

But there are, inevitably, some downfalls to the BWB design. Due to the plane’s wider interior, fewer passengers will have a window seat. There are also concerns that evacuating a blended wing aircraft would be more difficult, given that there would be fewer exit doors available.

Another challenge that BWB aircraft face is stability and control, due perhaps to the absence of a traditional tail. To counter this, designers may need to incorporate sophisticated flight control systems. There are also technical challenges around how to manage the pressurisation in a non-cylindrical fuselage. It is generally thought that the traditional tube-shaped design is better equipped to handle this.

And last, but certainly not least, is the question of whether such a design would ever pass through regulators. Conventional tube-and-wing aircraft, produced by manufacturers such as Airbus and Boeing which have been building them for more than half a century, must meet strict requirements before they can fly. Sometimes, these checks are so rigorous that they can lead to delivery delays. With a unique design, and chequered 100-year history, it is safe to assume there would be significant regulatory hurdles facing BWB manufacturers before they can safely take flight.

https://www.theage.com.au/traveller/travel-news/inside-the-revolutionary-jet-design-that-aims-to-change-air-travel-forever-20250708-p5mdgr.html