This article is from 2015, but I missed seeing it before.

If you’re going to absolutely insist on exploring the surface of Venus, there are two enormous problems that need to be dealt with. Problem number one is the enormous pressure, and problem number two is the enormous heat. At 90 atmospheres of pressure and just under 500 degrees Celsius at the surface, very little is going to survive down there for long. The best we’ve managed so far is about two hours in the case of Russia’s Venera 14.

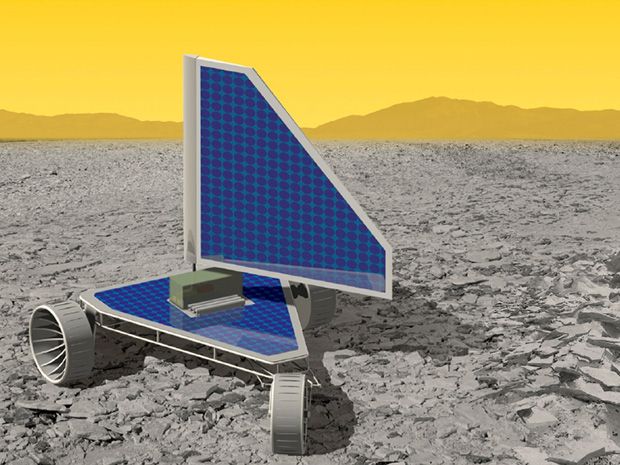

For a Venus lander mission, active cooling of most of the electronics would be necessary, but it would also need sensors, actuators, and microcontrollers that can stand up to Venus’ surface conditions. Trying to keep this stuff from immediate “puddleificaion” isn’t easy, but NASA has just thrown a quarter of a million dollars at a University of Arkansas spinoff to develop Venus-resistant chips for a weird little rover.

Ozark Integrated Circuits already has a chip that can tick along quite happily at temperatures of up to 350 degrees Celsius.

Photovoltaics won’t really work under all those clouds. But one slightly counterintuitive option might be a cooling system powered by a Stirling engine, which depends on the rover generating as much heat as it possibly can. Stirling engines convert a heat differential into mechanical energy, so the idea is that you’d bottle up a bunch of plutonium-238, which would heat itself to 1,200 °C through radioactive decay. With one side of a Stirling engine acting as a heat sink for the plutonium and the other side exposed to the comparatively frigid Venutian atmosphere, a Stirling engine could generate several hundred watts of power—enough to keep the electronics of a well insulated rover under 300 °C.

(Notes from mollwollfumble. Wind speed 10 km/hr, solar power 75 W/m^2 on the day side, a day lasts 243 Earth days. Batteries using molten salt and fuel cells will both work at those temperatures.)